Welcome to the latest issue of The Shamcher Bulletin, bringing you snippets from Shamcher’s writings that might help frame and context our experience of the world we live in today.

This issue features translation from a Norwegian book that mentions Shamcher’s wartime work. I take the liberty also of repeating here Shamcher’s autobiographical info, which he wrote for the book compiling bios of the original mureeds of Hazrat Inayat Khan. In that piece, he wrote:

When mureeds asked if Sufis should not be pacifists, Inayat replied: “If people of goodwill lay down their arms today, they will still fight: they will be forced to fight, and not in defence of their ideals any longer, but against them.”

Tally-ho

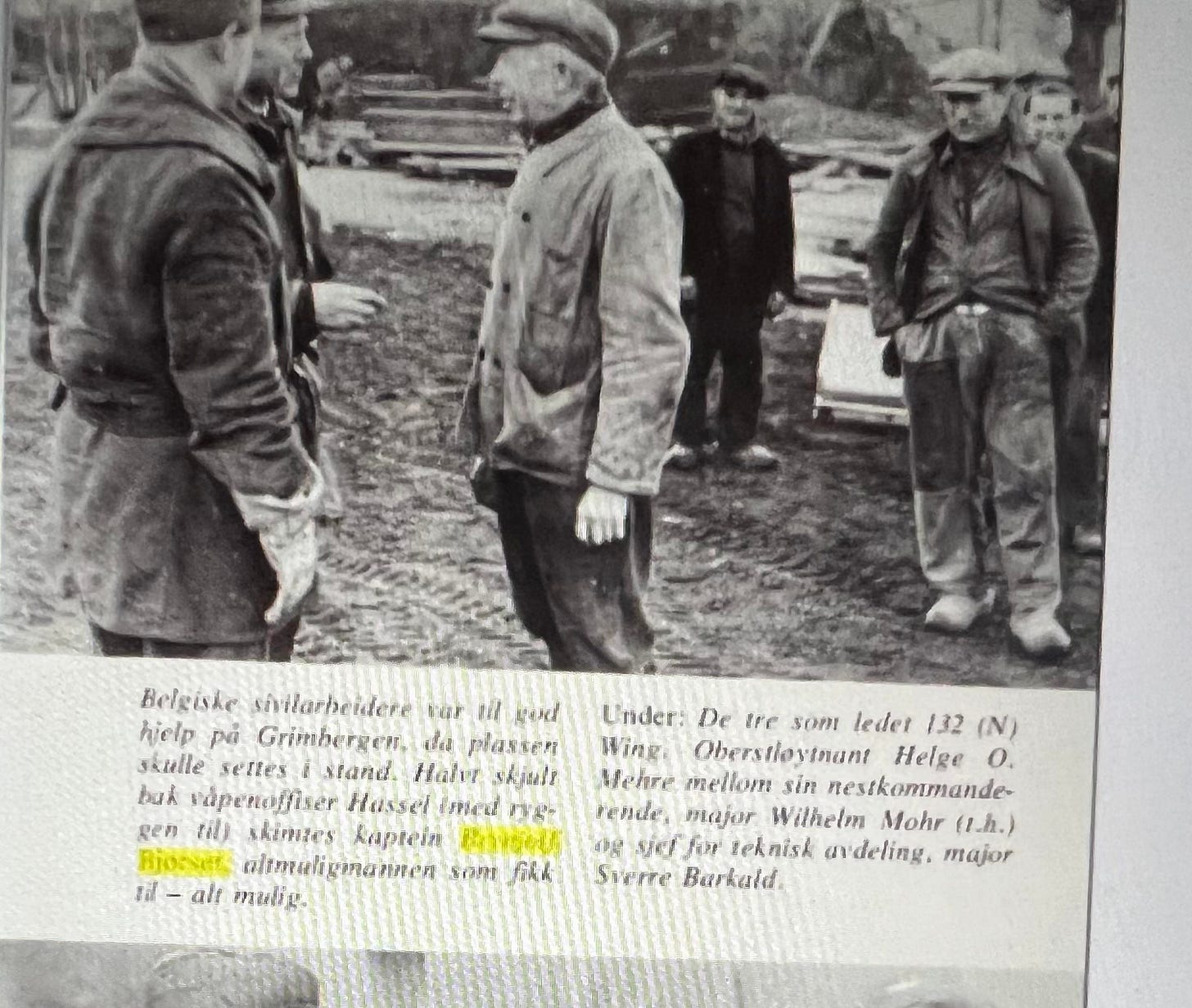

Kjersti Opstad in Oslo has kindly sent over translations of mentions of Shamcher’s wartime efforts, in the book, Tally-ho: Norwegian Fighter Pilots in Battle by Oddmund Ljone. The book also features a rare photo of him, taken while he was working with the Belgians at Grimbergen.

In the book he is described as “The Anything Man” because he could do anything, get or find anything. Kjersti said it could translate as “Jack of all Trades” - true, but that doesn’t entirely do him justice. I thought perhaps, “Renaissance Man” - fine, but that doesn’t cover the real down to earth action he was involved in. So it is back to “anything man” - a direct translation from the Norwegian.

Tally-ho! : norske jagerflygere i kamp (nb.no)

Shamcher can be seen in this photo, second from left. (from page 117)

Belgian civil workers were of great assistance at Grimbergen, when the place was being fixed and set up. Half-hidden behind Weapons Officer Hassel (with his back towards us) we can partly see Captain Brynjolf Bjørset, the anything man who could truly achieve anything. (translation from Norwegian)

Shamcher is further mentioned 2 times in this book. First at page 150-151:

But their everyday life was the war. Everything besides that was just a random glimpse of an occasional nice break. The war was always waiting for them afterwards. And the spitfire machine was standing there with its wide stripes in black and white around the tail and wings, reminding the pilots that the moments of joy always are the shortest ones in life.

Such memories one officer remembers nearly 40 years later. He says: We were operational from the 7th of October, I recall. It was at B60, just beside Brussels. We were quartered in a house that reminded us of a castle, with an eating space and a lounge. The only things we had of our own were our beds. The weather was starting to be cold and wet, and stone castles are not a pleasant place to stay in under such conditions.

But we had with us one man, Bjørset was his name, and he was a phenomenal engineer, right to the tips of his fingers. The whole way up north he had found the most incredible ways to lighten our burdens. He had put down flooring in the tents and had built small campsite fireplaces, beside building landing strips and parking spaces, besides helping the technicians so they could work.

We named him unofficial warden (vollmester) and made him Captain. It was also he who found our barracks (lemmebrakker) – only God himself knows where he got them, but he stole with an eager mind, drove out with trucks in the mornings and came back with the most incredible nice things, whether he had stolen them or used threats to get them, or if they were freely given to him we do not know.

Before the war, the “warden” had built roads and railroads in Persia, and he was extremely resourceful in crises. He learned to speak fluent Flemish in about a weeks time and that opened all the Flemish hearts and doors for him… and Wingen (an officer) went in with him.

We find another mention of Shamcher at page 214. They have now left Belgium for Holland and have just taken a short trip into an airstrip in Germany. This is in April 1945.

The airfield had been used by the Germans and was well-equipped, with barracks, offices and repair spaces, even if Allied bombs had put the buildings to ruins, so the camp looked to be in a rather horrible state. But the Norwegians made it into a cosy camp anyhow. “The warden”, Captain Bjørset, was delighted to find so many fabulous ruins to work with.

Unorganized?

Shamcher often wrote about his recollections of this effort, particularly as the experience related to hierarchies:

During World War II in liberated Belgium a crowd of civilians came to our air field and wanted to help. As an Officer of the Royal Air Force I was singled out to receive and accept them.

My commanding officer shook his head as he looked over the sorry lot, starved, almost skeletons, dressed in rags, rheumy eyes and noses, all looking sullenly down at the snow.

I told them I was sure they counted among them men who knew more than any of us in the armed forces about the things needed to be done and that I would form no organization, no hierarchy of supervisors and supervised. They went to work immediately without forming any hierarchy among themselves either.

When barracks were built the carpenters among them guided the work. When a plumbing job came along the plumbers came forward while the carpenters dropped back into the pool of general helpers.

Once a fully-organized engineering unit arrived from Britain and became impressed and dismayed by seeing this unorganized group work both faster and better, even though in addition to their work they prepared their own food and attended to all the housekeeping chores that the soldiers had had done for them by others.

From Autobiographical Information of the early mureeds of Hazrat Inayat Khan:

Bryn Beorse (Bjørset) (Shamcher)

In October 1923 when I was 27 years old and had traveled all over India looking for a teacher of Yoga, which I had studied from when eight years old, Sirkar van Stolk telephoned to me in Oslo: Would I translate a lecture to be given at the Oslo University by the World’s greatest mystic? “We know that you have traveled in India …”

A Theosophist friend insisted on going to the Grand Hotel together, where Inayat Khan was staying. I was irritated: this friend, too talkative, would ball up my serious interview about how to proceed with the translation – sentence by sentence or a script? Wondering how I would be able to get in my practical questions amid the heavy spiritual artillery fire I expected from my friend, I entered the room a worried man. – Inayat Khan looked up at us with laughing eyes. “Shall we have silence?” The gentle, sincere, almost apologetic tone of his voice contrasted the startling sense of his words. With a graceful bow he asked us to sit down. We seated ourselves in opposite corners of a sofa and he sat down between us and closed his eyes. So did we…I woke up, refreshed, when a bell rang. The interview was over, not a word was exchanged.

Next evening Inayat Khan gave his lecture and I translated it, after it had been given in full, without taking notes. People said I did not miss a word. I don’t know how.

I told him I liked his Message but I was already a member of the Theosophical Society and the Order of the Star in the East, so of course I could not join him. “No, of course not.” Four days later he came back from a trip. I said: “I think my membership in those other organizations was a preparation for something to come. I believe this may have come now. May I join you?” “With great pleasure.” Then he gave me practices and initiated me in a railway compartment. The people around us seemed unaware of what was going on.

I had played with God as a lusty playmate from early childhood, so could never be quite as serious and awed as some other mureeds and once, in the middle of the first Summer School in Paris, I suggested to Inayat Khan that perhaps I was not really fit for this life. He reassured me smilingly that I was, and protected me against assaults by other mureeds, in very subtle ways.

Murshida Green had asked us “What does Murshid mean to you?” “Well,” said I, “a friend, an example.” “Oh you don’t understand at all. Murshid is so much more than all that.” That same evening Murshid gave a talk but before he started he looked thoughtful, then said: “Before I start my talk I want to mention that sometimes a teacher’s best friends become his worst enemies – by lifting him up onto a pedestal and making of him an inhuman monster instead of what he is and wants to be: Just a friend, an example …”

Nevertheless, I want to ask forgiveness for my lack of respect. I even once asked Inayat whether we could give up the “Sufi” name on the Message since people misunderstood it for some Muslim sect. He said: “It could happen. But for the time being the name seems right to me, and if we did not put a name on ourselves, others would put a name on us and it might be worse.” More important is that Inayat pushed into my mind worlds of impulses that will take me eons to unravel and use.

When mureeds asked if Sufis should not be pacifists, Inayat replied: “If people of goodwill lay down their arms today, they will still fight: they will be forced to fight, and not in defence of their ideals any longer, but against them.”

In September 1926 I saw Inayat for the last time. I said: “I look forward to seeing you next summer.” “From now on,” he replied, “you will meet me in your intuition.” Then, during the first days of February 1927 I had a strange urge to travel to Suresnes, a three-four day trip by boat and rail from Norway. When I arrived others had had the same urge. Early on fifth February came the answer to why we had come. Now the Message was with us.

Inayat Khan often said “Mureeds who have never met me, never seen me, will often be closer to me than you, who know me as a person”. I am meeting such mureeds, closer to him, every day.

Berkeley, CA. U.S.A. From Shamcher’s autobiographical data. 27th July 1977.

Thanks for responding, sharing, and subscribing to these excerpts from the archives of Shamcher Bryn Beorse.

Feel free to reply to this post if you have any Shamcher stories, photos or correspondence to share.

The Shamcher Bulletin is edited by Carol Sill, whose newsletter, “Personal Papers”, is HERE.

If you like this post, please click the heart. And your comments are always welcome.

I found this fascinating. Snippets of history and thought. Of kindness and wisdom.

The closing paragraphs are etched in my mind (and heart) in such a way that I not only would recognize even just a phrase, instantly; but also, often spontaneously use phrases such as "with great pleasure" in appropriate everyday situations.